I remember an architectural coworker teasing me about my needing time to “take calligraphy classes or whatever”. I wasn’t taking a calligraphy class, and he knew it, but what struck me as so spot-on and funny about his dismissal of my extra-curricular pursuits is that I would have loved to have taken a calligraphy class then or now.

I remember an architectural coworker teasing me about my needing time to “take calligraphy classes or whatever”. I wasn’t taking a calligraphy class, and he knew it, but what struck me as so spot-on and funny about his dismissal of my extra-curricular pursuits is that I would have loved to have taken a calligraphy class then or now.

I’ve often pondered what it is about my “non-essential” creative endeavors that captivate me so. I look forward to them the way many anticipate a vacation on the beach or poolside. I find myself completely blissed out in a pin-hole photography class, a creative non-fiction workshop, or a plant-identification field-visit primer. What’s it all about?

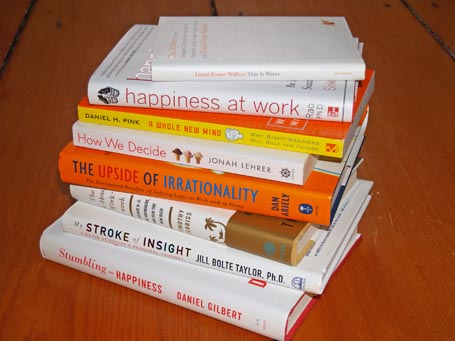

mystery-of-being-human books

For a while now, I’ve been turning to books for the answer. There’s been a series of what I’ll call mystery-of-being-human books taking up space on my nightstand over the years, starting first with Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert. Then, moving on to My Stroke of Insight by Jill Bolte Taylor, Ph.D., The 4-Hour Workweek by Timothy Ferriss, How We Decide by Jonah Lehrer, This Is Water by David Foster Wallace, The Upside of Irrationality by Dan Ariely, A Whole New Mind by Daniel H. Pink, and most recently Happiness at Work by Srikumar S. Rao, Ph.D.

Of course, I read other books in between these, but it wasn’t until finishing Happiness at Work a couple of weeks ago that I realized how much overlap there had been in the books cited above, to which I had gravitated. For me, they all seem to support an aspect of some inescapable truths; we all long for sublime connections to people, experiences and/or entities outside ourselves, and it is within our power to realize those connections. David Brooks describes such a drive, identified by current research in neuroscience, psychology, sociology and behavior economics, as “limerence”. Brooks explains in The New York Times that “… the unconscious mind hungers for those moments of transcendence when the skull line falls away and we are lost in love for another, the challenge of a task or the love of God”.

choosing how to perceive

Jill Bolte Taylor, a neuroanatomist, had a transcendent experience in the midst of a stroke, which struck the left hemisphere of her brain. In My Stroke of Insight she writes, “To the right mind [hemisphere], no time exists other than the present moment, and each moment is vibrant with sensation…Our perception and experience of connection with something that is greater than ourselves occurs in the present moment.” Her curiously euphoric experience of her right hemisphere while her left hemisphere was “offline” during her stroke, informed her recovery. She concludes, “I may not be in total control of what happens to my life, but I certainly am in charge of how I choose to perceive my experience.”

tendency toward me-centeredness

It’s perception of experience and our ability or inability to project that perception into an imagined future which interests Daniel Gilbert in Stumbling on Happiness. Ultimately, he concludes that we are each an unreliable predictor of our own happiness, and that the best path toward discovering future personal happiness is learning from others what makes them happy now. Tim Ferriss, author of The 4-Hour Workweek also recommends learning from others who have happily succeeded at what you aim to pursue. Daniel Gilbert acknowledges why this is harder than it sounds. He writes, “We don’t always see ourselves as superior, but we almost always see ourselves as unique.” He attributes this sense of our solitary uniqueness in part to the fact that “we experience our own thoughts and feelings but must infer that other people are experiencing theirs”.

These mystery-of-being-human books generally establish that our innate tendency toward me-centeredness is the opposite of the sublime connectedness to people, experiences and/or entities outside ourselves that we seek, however unknowingly.

in the zone

Even Tim Ferriss who seems only tangentially interested in the mystery of being human, appreciates the power of directed focus on a pursuit. His passions for unusual activities like tango competitions, Chinese kickboxing, and best-selling status, which periodically require his sustained attention, are what fuel his need to work only four hours a week. He advises, “Think of a time when you felt 100% alive and undistracted – in the zone. Chances are that it was when you were completely focused in the moment on something external: someone or something else.”

attentive and aware

David Foster Wallace acknowledges in This Is Water, a 2005 commencement address, “Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the center of the universe, the realest, most important person in existence. We rarely think about this sort of natural, basic self-centeredness, because it’s so socially repulsive, but it’s pretty much the same for all of us deep down.” He goes on to say that life’s challenge is more than learning how to think but “learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think”. This, he suggests, can mean reframing how we perceive something as banal as the supermarket, by imagining, for example, what other folks at the market may be going through. He ultimately extols the freedom of stepping outside your own skull in your daily life and investing in attention and awareness, now.

disciplined thinking

Jonah Lehrer tackles the challenge of exercising some control over our thinking in How We Decide. He writes, “Unless you are disciplined about what you choose to think about… you won’t be able to effectively think through your problem.” His concern is largely with the role emotions play in our decision making. He doesn’t divide it into a right-brain or left-brain issue at Bolte Taylor might. Nor does he explicitly get into a possible greater motivation -- to achieve the transcendence Brooks writes about -- in our decision making. Yet, he offers us the tools to better understand how we think. If properly applied, those tools could help us achieve a state of attention and awareness.

adaptation default

Dan Ariely, author of The Upside of Irrationality, delights in our all too human idiosyncrasies. His diverting book recounts a myriad of small and fascinating studies of human behavior. In one chapter, he identifies our impressive capacity for adaptation. He notes, “The bottom line is that we have only a limited amount of attention with which to observe and learn about the world around us – and adaptation is a very important novelty filter that helps us focus our limited attention on things that are changing and might therefore pose either opportunities or danger.” Ariely’s experiments demonstrate that we should slow down pleasurable experiences to deny adaptation and thus make them more pleasurable and speed up annoying ones to invite adaptation and thus reduce their annoyance. The takeaway: slow down an experience to prevent from adapting to it and thus keep engaged – attentive and aware, the state of mind Foster Wallace advocates.

high concept and high touch

Daniel H. Pink advocates for A Whole New Mind. He sings the praises of right-directed thinking, which, according to Pink is “a form of thinking and an attitude to life that is characteristic of the right hemisphere of the brain – simultaneous, metaphorical, aesthetic, contextual, and synthetic”. He sees right-directed thinking as critical to a new age he describes as “high concept” and “high touch”. He explains, “High concept involves the capacity to detect patterns and opportunities, to create artistic and emotional beauty, to craft a satisfying narrative, and to combine seemingly unrelated ideas into something new. High touch involves the ability to empathize with others, to understand the subtleties of human interaction, to find joy in one’s self and to elicit it in others, and to stretch beyond the quotidian in pursuit of purpose and meaning.” He notes, “Indeed, our capacity for faith – again, not religion per se, but the belief in something larger than ourselves – may be wired into our brains. Perhaps not surprisingly, this wiring seems to run through the brain’s right hemisphere.”

reframing to reinvent

Srikumar S. Rao, Ph.D.’s Happiness at Work applauds the values of other-centeredness, as opposed to me-centeredness, too. Rao also emphasizes our potentially constructive abilities to control how and what we think. Unfortunately, the tone of his book smacks a bit of smarmy self-helpese, but Rao does assemble a number of worthy lessons which also include: don’t label things as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ – it’s often too soon to tell; manage yourself (your time) and your ability to stay focused; your attitude influences how you see the world; the intention and intensity of your actions effect your sense of well being more than your accomplishments; you have the power to change the story you create for yourself about yourself; etc.

meaningful continuing education

The best moments of these books tap into the essence of what makes us tick and our role in the ticking. They’re great primers on mindful thinking, and have led me to understand that continuing education may help some of us tick. A calligraphy class, as silly as it sounds, may be more than an extracurricular pursuit; it may be an opportunity to add meaning to life. It, or something like it, may allow for transcendent moments where we’re fully engaged and present. It might briefly satisfy our limerence. I, for one, can’t wait to sign up for my next continuing education workshop, whatever it may be, and to delve into the next mystery-of-being-human book. There’s always more to learn.

by Katie Hutchison for House Enthusiast